200,000 Ugandans have signed up to a company believing it will cure all their illnesses and help them make a fortune. But it is more likely to do the opposite.

By James Wan.

Kampala, Uganda:

Kampala, Uganda:

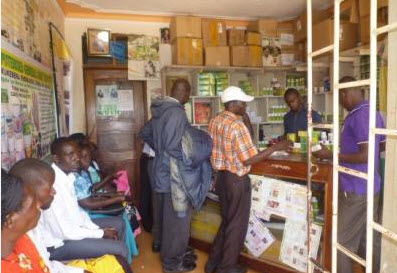

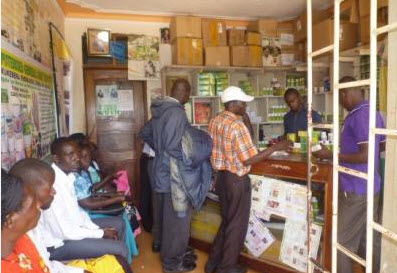

On the corner of a bumpy, red-soil road in the rural town of Iganga in eastern Uganda, there lies a small store. A handful of people mill around the entrance in the glaring sun, waiting their turn to enter. They are the main source of activity on this placid street, but their patient presence barely betrays the hubbub within.

Inside, almost a dozen people sit crammed on makeshift benches around two edges of the stifling room. Most of the remaining space is taken up by a shop counter, behind which are shelves piled high with vibrantly-coloured health products covered in Chinese characters.

A couple of customers compete with a baby wailing as they read out lists of products to the shop attendants who pick them off the shelves. Every now and then, the door in the corner opens. Someone steps out, usually holding a piece of paper, and the person sitting closest steps in.

Beyond that doorway is an even smaller room, windowless and illuminated by a single light. As I peer in, three people are undergoing diagnostic tests, a woman is standing on a machine that hums loudly as it vibrates, and a few more patients are waiting slumped along the wall.

Wasswa Zziwa Edrisa − or “Doctor Wasswa” as he is known here − stands in the centre wearing a fresh, chequered shirt on his back and an unwavering grin on his face. With the easy charm of a seasoned salesman and the swaggering self-assurance of Uganda’s national bird and symbol, the crested crane, Wasswa welcomes me in.

“I will show you how we help so many people,” he says, beaming. “Let me show you the machines.”

“This is one of the scanners,” he explains, pointing to a piece of kit that looks a bit like a 1970s radio. “It shows everything. We can see if you have diabetes, kidney deficiencies, liver problems, eye problems. Everything.”

Wasswa explains that the test works using a traditional Chinese understanding of the body whereby different points of the hand relate to different internal organs. We watch as an attendant prods a patient’s left palm with a metal tip, making a little meter light up. When the light goes green, he explains, it means that part of the body is fine, but if it goes orange it indicates a problem.

Next Wasswa points me to the corner where a woman is standing on a small machine and holding onto a pair of handlebars to which she is harnessed. Her whole body blurs in the dim light as the platform beneath her vibrates rapidly, its droning buzz filling the room.

Similar machines can be found in many gyms these days and are meant to help tone muscle, but the uses Wasswa presents are quite different.

“This is a blood circulation massager,” he announces. “You see how she sweats. It opens the vessels and deals with paralysis. It helps people with stroke.”

Wasswa then shows me another diagnostics machine, this one connected to a laptop. As the patient holds on to an appliance plugged into the computer, pictures of different organs flash up on the screen for a few seconds each as a dial next to it oscillates erratically. After a minute, a one-page document pops up, listing how well his organs are functioning.

In the airless room, Wasswa runs through a few more devices − a face pain remover, a blood pressure reducer, a necklace that removes radiation − before squeezing past bodies and chairs to get back to the first patient we met. By now his diagnostic test is complete. He tells me that he came to the store because of some mild pain around his mouth, but Wasswa breaks the news that there are more serious things about which he ought to be concerned.

“Ah, he has a problem with his spleen,” says Wasswa, nodding knowingly. “At times, he gets constipation and some swelling in the legs and arms. There is also some paralysis in the legs. He gets headaches. At times he feels dizziness. His brain arteries need to be detoxified. He has kidney deficiencies. He has bad chest pain. He has high cholesterol. He has poor circulation. And he has problems with his stomach.”

The roster of the young and healthy-looking patient’s conditions seems extreme, but Wasswa is not perturbed.

“He needs to improve his circulation by using our machines and he will need to take our products. If he uses them, he will be fine,” he reassures.

Back in the light and noise of the waiting-room-cum-pharmacy, Wasswa shows me some of these products. He picks goods off the shelves, ranging from capsules to toothpastes to body creams, and stacks them on the counter as he explains what they each do. “This takes away all the radiation in your body. This helps with diabetes. This treats ulcers. This is for slimming. This adds more white blood cells to your system. This is for people who are mentally disturbed,” he says.

“These medicines are good for everything,” he concludes finally, the pile of products on the counter now complete. “If you have cancer, we can help. If you have HIV, we can help. Even if you have a hernia or a tumour or appendicitis, you just take our products and they will disappear.”

Wasswa (right) piles TIENS products up on the counter of the store in Iganga.

This small store in eastern Uganda employs a handful of staff and, according to Wasswa, receives dozens of patients each day. Wasswa is also frequently heard on local radio advertising his services and has made quite a name for himself in the area. He was previously a school teacher and says his parents were “peasants”, but now, in his 30s, he is anything but. These days, Wasswa drives a shiny four-wheel drive, wears sharp suits and even goes on jet-setting trips around the world. All this makes him quite the exception in Iganga, but across Uganda, this young ‘doctor’ is by no means a solo pioneer and his store is by no means unique.

Similar stores can found all across the country, from Kasese in the west to Soroti in the east, and from Gulu in the north to Entebbe in the south. There are four such outlets in Kampala alone. These stores offer the same diagnostic tests, stock the same range of products, and above all their doors, there hangs the same innocuous green and orange sign which reads: “TIENS: Together We Share Health And Wealth.”

TIENS − also known as Tianshi − is a multinational company based 10,000 miles away in the Chinese metropolis of Tianjin. It was founded in 1995 by Li Jinyuan, who has since become a billionaire from the venture. The company has established branches in 110 countries including 16 in Africa, employs over 10,000 staff globally, and reportedly enjoys net profits worth hundreds of millions of dollars each year.

TIENS first began tapping into the Ugandan market in 2003 and it has grown steadily ever since. There are now around 30 stores across the country, TIENS distributors regularly engage in outreach programmes to rural communities, and according to the company’s national chairperson, Kibuuka Mazinga Ambrose, TIENS-Uganda has an annual turnover of around $6 million.

The company has even bought the most prominent advertising spot on the Health Ministry’s official calendar, a particularly brazen move given that none of its outlets are registered health facilities.

Patients who come to TIENS seek help for a whole range of conditions − from malaria to paralysis − but they tend to tell similar stories of how they arrived here. Typically, they say that they first went to public facilities (some told me they had even visited two or three), but were either not seen to or found the treatment ineffective. TIENS is almost always a last resort. But in a country whose healthcare infrastructure is riddled with chronic problems and which, by some measures, ranks as one of the worst in the world, the last resort is often one that needs to be taken.

In many areas of Uganda, public health facilities are virtually inaccessible, while those who do manage to reach them may find their walls crumbling, their clinics under-staffed, and their shelves bereft of drugs. Although the government has promised to invest more in the sector, much of the country’s healthcare infrastructure is in decay. Doctors and nurses are over-worked and underpaid, and although services are meant to be free, in reality patients face many hidden costs.

In this context, stores like Wasswa’s − with its quick turnaround, attentive staff and fully-stocked shelves − offer an appealing alternative. The always conclusive diagnostic tests are highly convenient; attendants’ claims about the healing powers of TIENS products may well be reassuring; and many patients say the fact the medicines travelled thousands of miles from China suggest they must work.

Many customers who use TIENS products also insist that they do work.

A patient uses a “blood circulation massager.” In gyms, these are known as Power Plates.

On the Friday morning after my tour of Wasswa’s clinic, the courtyard next to the outlet is packed. Over a hundred people sit on plastic chairs facing forwards while latecomers lean against the back wall. A red tarpaulin sheet shields the crammed attendees from the sun and gives the whole atmosphere an eerie pink hue.

‘Doctor Julius’, a man in his late-30s with an intense glare and impatient demeanour, stands at the front. He has just finished explaining the healing powers of TIENS toothpaste − which as well as cleaning teeth, can be used to treat ulcers, angina and skin problems amongst many other conditions − and he invites attendees who have used the product to give testimony. Four hands go up immediately.

“I had terrible problems with my teeth,” says the first speaker. “I went to see doctors but a new tooth had to be uprooted every week. When I started to use TIENS toothpaste, the pain went away.”

The next patient tells a very similar story before two mothers relay how the toothpaste cleared up their respective children’s skin rashes and burns.

Every now and then over the next few hours, many more attendees are invited to recount their experiences of using TIENS products. We hear how a man with back pain can now walk, how another man was cured of vertigo, and how a woman’s child was once bed-ridden but is now running around. At one point, Wasswa looks particularly pleased as a mother tells of how her young son − who she had taken to three separate public healthcare facilities before he was cured of cerebral malaria by TIENS − now wants to change his name to ‘Doctor Wasswa’.

“You see, these products work,” Wasswa announces after one of the testimonies. “At hospitals, they will ask you how you feel, but here, we tell you how you feel. At hospitals, they treat signs and symptoms. Here, we treat causes. At hospitals, they give you medicines made from chemicals which are harmful and can give you ulcers. Here, we use herbal medicines which have no side-effects.”

“This is real,” he continues. “This is Chinese herbal medicine based on 5,000 years of traditional medicine and it works.”

A patient gets tested by a TIENS attendant.

In Kampala, I test this out for myself. I visit a couple of the company’s stores, nestled in the city centre’s endless bustling plazas, and in one of them, managed by an intense man named Frank, I get tested.

Frank, the self-declared “best in the business” at doing diagnostic tests, seems thrilled at my presence and bundles me across to the end of the room. He sits me down and pulls across a thin curtain to give us a modicum of privacy from the handful of waiting patients. He takes out a battered looking hand-held device, pushes a 9-volt battery into its back and plugs a wire into it that branches into two metal tips. He gives me one of the electrified points to hold in my right hand and says he will use the other to press points on my left palm. With a grave look on his face, Frank instructs me to tell him when I feel a tingling. This seems to be a more basic version of the first test I’d seen in Iganga.

To begin with, I report whenever I feel something, which is every single time the tip touches my hand, completing the basic electric circuit. Frank nods excitedly when I do so and explains that I have a serious problem in whichever part of my body he is testing. After a while, however, I decide to stop reporting every time I feel a tingling. Frank lets me get away with one, but after that he frowns when I stay silent and simply keeps the metal point on my hand until I give in, sometimes rubbing my hand and even licking the metal tip if I am being particularly resistant.

In the end, Frank writes out a list of around 25 health conditions including “liver disorder,” “STROKE,” and “enteric fever [aka severe typhoid],” and prescribes a roster of products that comes to over USH 1 million ($400).

Before committing to his costly regimen, I decide to get a second opinion.

In the bright, clean reception of Beijing Clinic, a private health facility in Kampala, I relate my experience to a young Ugandan doctor, who trained and qualified in China, specialising in traditional Chinese medicine. The doctor, who prefers not to be named, laughs as I explain the machines I saw in Iganga and the test I underwent in Kampala. “No machine can test all those things like they claim,” he says.

Next, I show him the TIENS Information Guide, a booklet from which it seems Julius and Wasswa get most of their information. On page 3 of the booklet, a short disclaimer warns: “Tianshi Company does not make any medical claims whatsoever.” However, the next 60 pages are filled with bold declarations about the powers of its products and instructions on how to treat different diseases.

“Whatever this is, it is not Chinese medicine,” says the Chinese-trained doctor with a combination of amusement and incredulity. He chuckles as he reads how TIENS medicines are supposed to treat about a dozen different conditions each, from preventing cancer to reversing impotence to promoting “the growth of children’s reproductive organs.”

However, the doctor’s amusement soon turns to horror as he reaches the section of the booklet advising distributors on what steps to take when patients are suffering from different diseases. TIENS customers are typically encouraged to undergo diagnostic tests in store, but most who go to TIENS have previously been to hospital and know some of the conditions from which they are suffering. The company guide offers clear and easy instructions on what they should be prescribed.

Of the few hundred conditions listed − which span from AIDS to Yellow Fever − a handful include the recommendation to ‘see a doctor’. But the rest just list a few products to be taken.

“This is a death sentence,” mutters the doctor, falling silent.

One of the most repeated claims by TIENS distributors is that because the products are ‘herbal’, they have no side-effects. This assertion is used to elevate them above Western medicines, which they say are made from chemicals and so can be harmful, but the claim is also used to suggest that there are no dangers involved in taking them.

“Even if I tell you to swallow one and you swallow four, there will be no problems,” Wasswa had insisted. But when put to the Chinese-trained doctor in Beijing Clinic, he just shakes his head. “That is a flat out lie,” he says.

He recalls that last year, he was consulted by police after a man suffering from kidney problems died suddenly from liver failure. A toxicology report found that he had had a toxic overdose and it was suggested that the TIENS supplements the patient had been taking without his doctor’s knowledge had either caused additional problems or reacted badly with other medicines. The man’s family could not afford to get a more detailed medical report, however, and declined to take the matter further.

At another private clinic in Kampala, Dr Wen, a highly-regarded practitioner with three decades experience, is similarly concerned. “This is not medicine,” he says, “but it is still dangerous. Everything has side-effects. Even herbal medicines and herbal supplements used wrongly can kill.”

I contacted Uganda’s Health Minister, Ruhakana Rugunda, repeatedly for comment, but received no reply.

−

Apart from the story of the kidney patient, I didn’t come across other rumours of deaths, but cases of the products not working as miraculously as promised were easy to find. After all, TIENS products are not medicines. Some of the company’s goods have been registered with Uganda’s National Drugs Authority, but as ‘food & dietary supplements’. In fact, stories of TIENS products not fully working were even common amongst some of TIENS most ardent fans.

Back in Iganga, with the courtyard seminar over and Wasswa busy talking to a small circle of attendees eager to hear more, Sarah*, 25, moves towards the back of the courtyard closer to where I am sitting.

During the seminar, she had given testimony telling of how she’d taken her baby boy, who was suffering from sickle cell anaemia, to several hospitals before she came to TIENS. Many of those who told their stories directed them matter-of-factly at Julius or Wasswa, but Sarah had turned to face the crowd and spoken passionately as she’d explained how the products worked wonders.

Asked a few more questions after the symposium, however, her story reveals itself to be far less straightforward. It transpires that her son is still ill. So ill, in fact, that she recently quit her nursing job to look after him full-time. Sarah nevertheless insists that the TIENS medicines work and says the reason her son is still suffering is because his treatment is incomplete. She bought half the products the boy needs for a full recovery but is struggling to find the money to purchase the rest.

Robert, 30, tells a similar tale. He too claims to be a firm believer in the healing powers of TIENS, and acted as my translator throughout the seminar, seemingly on Wasswa’s instruction. Robert says that he came to TIENS with kidney problems and maintains the products worked where hospital treatments failed. Like Sarah’s son, however, he admits that he is still in pain. Firstly, he attributes this to the fact that his kidney treatment is incomplete; he too has had financial difficulties. Secondly, he explains that the TIENS diagnostic test revealed his kidneys are not his only problem; while his original condition may have improved, he now knows he is suffering from other conditions that need to be cured too.

Sarah and Robert reveal that they have each spent USH 460,000 ($180) on products so far, paying in instalments from what they could borrow or scrape together. Sarah says she needs USH 500,000 ($200) more to complete her son’s treatment, but doesn’t know where the money will come from given that she is now jobless and that the father of her son is in school. Robert says he needs around USH 200,000 ($80) more, but says that as a “peasant”, he too will struggle.

“I haven’t balanced it well,” he says, “but I hope it will balance out soon. I am still feeling pain.”

Attendees gather to listen to Wasswa in the courtyard in Iganga.

It is not a coincidence that Robert, Sarah and a few others who spoke to me had all purchased exactly USH 460,000 worth of products. Nor is it an inexplicable peculiarity that individuals with no reliable source of income had shelled out what little they had, and more, on TIENS products. After all, TIENS is more than just a supplier of health supplements.

In the symposium in Iganga, once Julius had waxed lyrical about various products, it was time for Wasswa to take over the stage to talk about another benefit of TIENS. Though not before Julius had the opportunity to rouse the crowd.

After finishing his demonstration of TIENS’ disease-curing sanitary pads, Julius put down the product and strolled ponderously along the front of the courtyard before turning to face the audience. “Tianshi!” he shouted suddenly. “Together we share!” came back the reply on cue, a hundred voices amplified by the concrete walls. “Tianshi!” Julius proclaimed a second time, a little louder. “One dream!” came the soaring response. “Tianshi!” yelled the doctor a third time. “The best of all!!” bellowed the crowd.

Next, Julius taught the audience a new trick. Since all points in ours palms relate to different internal organs, he explained, clapping stimulates the whole body and works as a kind of “first aid.” He held his hands apart and, together with the crowd, clapped out a rhythm that crackled across the courtyard. Julius explained that the louder you clap, the greater the benefits to your internal organs, before holding out his hands and going again. And again.

Finally, looking satisfied, Julius completed his session and handed over to Wasswa.

“TIENS is not just good for your health,” the salesman proclaimed, taking to the stage, “it is also good for your wealth. If you register with TIENS, they will start to pay you. You come here for treatment, but over time, you will start to get a salary.”

Over the next few minutes, Wasswa explained that this is what he had done and that he was not only receiving thousands of dollars every month now, but had been taken on international trips by the company, received huge cash bonuses and been given a brand new car.

“When you reach a certain level, you start earning,” he said. “And it does not matter if you have no qualifications or education. TIENS does not care if you are educated. TIENS only cares how many products you buy and how many people you recruit.”

Wasswa said these words with a weighty earnestness, but they were not news to half the courtyard. Robert, Sarah and many others around them − all recognisable by the golden lion-shaped badges they were wearing − were not just TIENS patients, but members and distributors already. They were here on Wasswa’s instructions to give testimony and help convince others to join too. For these returning members, TIENS is not just a medical supplier, but a livelihood, an investment, and a chance to follow in Wasswa’s jet-setting footsteps.

−

Sitting behind his desk at the TIENS-Uganda headquarters, located at the top of King Fahd Plaza on a busy street in Kampala, Kibuuka Mazinga Ambrose is delighted to explain how the business model works in more detail.

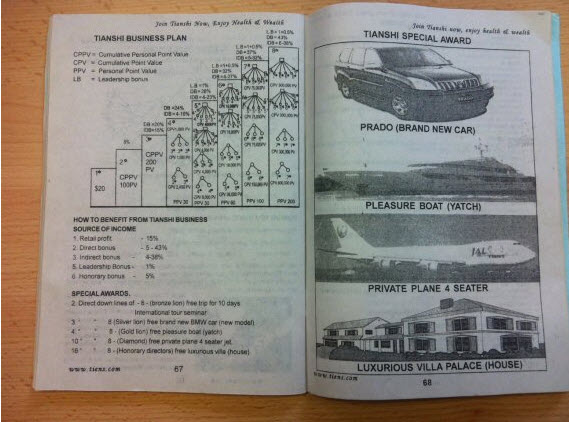

“Anyone can join,” says the company chairperson, wearing a bright yellow TIENS-branded cap. “All you need to do is pay a small initial fee of $20.” Once you have done this, you can buy products at wholesale prices and sell them on at a profit. However, this is just the start, he says. You don’t get rich by selling a few bottles of herbal supplements. Under TIENS’ model, there are eight ranks and you need to move up the levels to really start enjoying the benefits.

The first few levels can be reached simply by buying more products, which essentially brings with it a small discount on goods. However, to get to the bigger rewards, you need to start recruiting others. This way, you receive a commission whenever they make purchases and also get rewarded if they recruit their own followers.

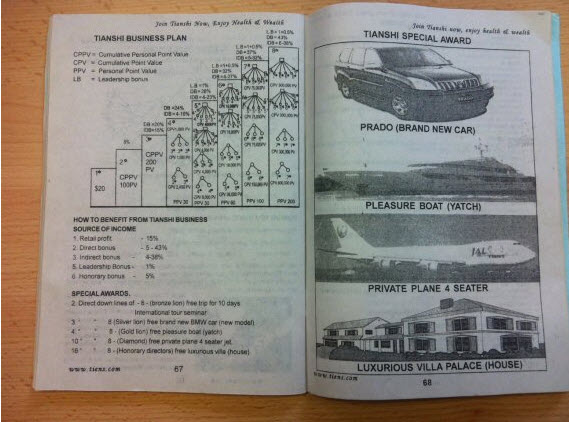

The more people you recruit and the more they recruit in turn, the higher you move up the rankings, and soon you can just sit back and watch as the commissions roll in. Furthermore, once you’ve reached the 8-star level and keep growing your network, you will eventually become a Bronze Lion, then a Silver Lion, then a Gold Lion, and enjoy rewards of cash prizes, international trips, a brand new 4×4 car, a luxury yacht, a private jet, and finally a “Luxurious Villa Palace.”

“It’s all about growing your network; their success is your success,” says Ambrose cheerily. “TIENS does not care who you are. Anyone can do it, and there is no limit on what you can earn.”

As the TIENS Guide puts it, joining the company means: “You stop struggling financially,” there is “little risk of losing”, and “if you work for 5 years you can retire.”

The TIENS-Uganda Information Guide explaining the business model.

According the company website, over 200,000 Ugandans have joined TIENS, eclipsing even the number of government school teachers in the country.

Given Uganda’s high rates of unemployment − youth unemployment is over 80% according to some estimates − the appeal of membership is clear to see. Decent jobs are scarce and rags-to-riches stories like Wasswa’s are even scarcer.

Furthermore, the company’s image is significantly helped by the Ugandan government. Not only does TIENS advertise on the Health Ministry’s calendar, but according to Wasswa, around ten MPs are members of the company and at the Iganga seminar, Stephen Wante, the mayor of Bugembe, made a guest appearance. In 2011 meanwhile, Vice-President Edward Ssekandi officiated a ceremony in which a distributor was awarded a car and organised for TIENS to donate some of its products to a government health centre. A photograph of the Ssekandi shaking hands with TIENS’ president also has pride of place on the company website.

However, despite all of TIENS’ promises of wealth and perceived legitimacy, actually making money from the scheme is virtually impossible. At the TIENS headquarters, where members can print out their balance sheets, many leave the office holding spreadsheets indicating that they are owed almost nothing, if anything at all. Meanwhile, back in Iganga, several members who had joined several months ago, attended every biweekly seminar, bought lots of products, and gone on recruitment drives, revealed that they had not earned any notable income either. It seems many others have also abandoned the scheme after finding they could not make it work.

According to most TIENS members − both those who are profiting and those who aren’t − the reason for these failures is simple: the individual did not work hard enough. When I asked Sarah why she thought she hadn’t made any money after being a member for five months, for example, she hesitated before Robert helpfully chipped in to say “it means she is not performing well.” Yet Robert had barely received any income either, despite having been a member for six months and having recruited nine people. Other members who had yet to make money also suggested their situation was down to bad luck or poor performance.

This feeling was perhaps most starkly expressed after the seminar as I spoke to Wasswa within earshot of three members, all of whom had been distributors for up to six months yet not come anywhere close to getting a decent income. I asked Wasswa how long it typically takes to break even. “Some people can take a month, but sometimes maybe two months,” he replied. What if someone has been working hard but hasn’t started getting an income after 6 months, I followed up. “Six months?” Wasswa exclaimed. “No, it’s rare. Very rare. If someone is serious, they should be on a high level and earning well after six months.”

I looked over at the three recruits who all just stared at the floor, looking sheepish and, I thought, ashamed.

The pharmacy in one of the stores in Kampala.

The reality, however, is that failure under TIENS is not the individual’s fault. In fact, for the vast majority of members, the business model is designed to fail. TIENS in Uganda appears to be little more than thin-veiled pyramid scheme.

Recruiters emphasise that to join, all you need to do is pay a $20 membership fee. But in reality that is only the start. Members have to buy products to move up the rankings and then continue to buy goods to keep their accounts open.

Members could make money selling these products, but the idea of shifting all these goods is a non-starter. Not only does each distributor have to compete with 200,000 other sellers as well as 30 well-established stores, but it doesn’t even make economic sense for customers to buy from individual members when they could sign up to TIENS themselves and get much lower prices anyway.

This is perhaps why Wasswa and other recruiters barely even mention selling products and why the emphasis instead is very heavily on “growing your network.” The incentives for signing up new members are higher than those for sales; the training sessions teach recruits how to sell membership rather than goods; and the TIENS Guide’s main piece of practical advice is a 6-step plan of how to “make a name list of at least 100 in a shortest time possible.”

If not from selling products to the public then, the bulk of the money in the TIENS system comes members’ own pockets as they pay to join, pay to move up the rankings, and pay to keep their accounts open. And it is this same money that finances top-level distributors’ huge salaries, shiny new cars and trips around the world. Given all the money in the system comes from members, the only way this tiny elite profits is because the rest of Uganda’s 200,000 members do not.

TIENS refer to itself as a ‘multi-level marketing’, but in reality it seems to be an unsustainable and fraudulent pyramid scheme designed to extract money from the many to pay the salaries of a few.

I later contacted Ambrose, Wasswa and Jamba George, another 8-star recruiter, for their response to these allegations, but they all declined. The manager of TIENS-Uganda, a Chinese expatriate, and the company’s global headquarters in Tianjin did not make a comment either.

It should also be noted that TIENS is not just in Uganda, nor is it the only scheme of its kind. The American firms Forever Living and GNLD also deal in health supplements and follow a multi-level marketing model, while TIENS’ presence on the continent seems to be particularly strong in West Africa, Ethiopia and Zimbabwe. It is further notable that TIENS has offices in many Western countries, though the products there seem to be marketed more directly as mere food supplements.

−

Back in the courtyard in Iganga, Robert is listing the products he was prescribed six months ago. Like so many others faced with Uganda’s struggling healthcare system, Robert ended up seeking alternatives and eventually ended up at Wasswa’s busy but welcoming clinic.

The products worked, Robert insists. Up to a point. He just wishes, he says, that he could finish the treatment and be fully cured of his kidney problems as well as the other health conditions detected by the diagnostic test he underwent. But he cannot afford it.

Robert has no other jobs − he says there are hardly any jobs available in the area − and has five children to support. When he joined the company half a year ago, he thought TIENS was the answer to all his prayers, but he is still in pain and deeper in debt.

“Money is a problem, he says. “It is not easy to recruit people and I spend USH12,000 ($5) every week on transport to come to these seminars.”

I ask him why he is still part of the company despite losing money each week. He pauses for a moment before answering, “I believe I will balance my accounts soon. And I am close to moving up to the next level when I will be able to earn more.”

He explains that a technical misunderstanding delayed him moving up a rank, but that it should be sorted out soon. I point out that even if he moves up a level and earns slightly more than now, he will still be earning a tiny fraction of what he has invested. He nods in agreement, but adds, with a faint smile, “But with TIENS, time is on your side.”

But what if it still doesn’t work out, I push. What if Wasswa is the exception that proves the rule? What if it never works out?

Robert looks me in the eye for a few seconds before gazing out across the courtyard where a few groups of attendees are still standing around chatting.

“If the money defeats me, ” he says quietly, turning back to me, “I will disappear.”

*some names have been changed to protect interviewees’ identities.

Photographs by James Wan.

This article was made possible by a grant from the China-Africa Reporting Project managed by the Journalism Department of the University of Witwatersrand.

Amendment [12/06]: A paragraph about the network sizes required to move up the rankings was removed because some of the figures didn’t take into account the fact there are alternative options for promotion.